This is the second in an occasional series that will strive to demonstrate that Madrid is more than the three Ps: The Prado, the Palacio Real, and the Plaza Mayor. Madrid is a diverse city, full of hidden delights. This is one of them and should not be missed by any that want to get more than a superficial idea of what has made Madrid what it is. The three Ps are indeed a very integral part of any visitor’s itinerary, but, as you will see, are not be the only places worth a visit.

The Museo de la Ciudad (The Museum of the City.)

The Museo de la Ciudad (The Museum of the City.)

People have been living in the Madrid area since prehistoric times. Of course, it is well known the Romans had a settlement here, although for them Segovia and Alcalá de Henares were more important. Archaeologists have discovered artefacts that cover a wide spread of centuries. However, it is thought that the origins of the modern city didn’t begin until around the 9th century when Muhammad the First ordered the construction of a small palace somewhere near the present day site of the Palacio Real.

Around this palace, a small town grew up and was known as Al-Mudaina. Not far away was the Manzanares River, which the Arabs called Al-Majrit, which means “Place of Water”. From this, the name was taken to refer to the whole area and slowly changed over time through Majerit into the modern name Madrid.

If you have any interest in the city beyond the café and bar society and the meccas of fine art, then the Museo de la Ciudad, the Museum of the City, should enter into your itinerary. In this light and airy modern building are housed some wonderful exhibits, helpfully arranged in chronological order, that explain not just the history of Madrid, but how it works and how it celebrates its existence.

It is not a museum crammed with strange object, although there are a few. It does not ram the history down your throat. Set on four floors set about a high atrium the displays allow you to discover for yourself the wonderful story that is Madrid. Neither, for the non-Spanish visitors, will you have to delve into your dictionaries to understand the exhibits, as displays are simple and it’s pretty much self-evident what you are looking at.

When I first visited the museum, I was taken by an enthusiastic Spaniard who insisted we started on the top floor. The lifts are modern and swift. In fact the place is a shining example of how to provide easy access to anyone, whatever their fitness. (Although there are there’s a tricky little area of uneven floor on near the Canal de Isabel II exhibit, which explain how Madrid is supplied with water.)

The top floor is recent Madrid. It is a testament to the art of the model-maker. Whole swathes of the city have been miniaturised. The detail is amazing. We spent ages looking over a model of the area that runs either side of Paseo de la Castellana finding the apartments and offices of friends. For me the scale model of the bullring at Ventas, which is close to where I live is quite superb.

Here too, you will find models of buildings and plazas that have since been changed since the model was made that give rise to cries of, “So that’s what it used to look like”.

But a city is more than its buildings. The citizens live, work, play and dress here. There are exhibits of many of the old ways of doing things – and the quaint and curious implements they used. There is a display of beautiful clothes, including the traditional “Vestido de Chulapa”, the tight, sexy dress worn by Madrid ladies for the fiestas of San Isidro and San Antonio.

(Now here’s a fascinating tit-bit, which will probably get me into hot water with my Madrid friends, but I can’t resist. In Spanish, if someone is described as “Chulo” it means that they are a bit full of themselves and quite derogatory. And Madrileños are often described, by the rest of Spain, as just that. Whether the name of the costume is derived from the epithet, or vice-versa, I don’t know. Men also wear a special form of dress at these festivals, but they all look like Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins!)

Let’s descend a floor. Here. This is about how Madrid started and developed. We find ourselves at home with the first settlers in their rough huts. We visit the Romans in their villas Romans and see the Moslems at work. We find the comparative luxury of the bourbons and the men and women who made Madrid what it is.

What wonderful imagery is here: Pictures vividly show life at its best and its worst from Autos de Fe to magnificent parades. There are portraits of great men and women, architectural plans, exquisite carvery and beautiful fans. The ladies of the Bourbon court were the height of fashion and seemed very comfortable in their luxury.

One floor lower and we see how they did it! Technology comes into play. There are sponsored exhibits from the water, telephone and electricity companies.

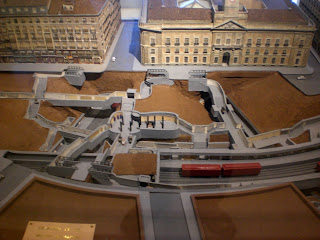

We see how the Metro was constructed and why it became necessary to travel under, rather than over Madrid’s increasingly crowded streets. You can take a seat on a tram and watch a film and there’s a model of the construction of the metro station at Sol which demonstrates exactly why the Madrileños describe their city as being like a gruyere cheese! (And becoming more so.)

The latest display is about Barajas airport. This is a triumph of the art of the model maker. Since the opening of terminal four Madrid’s airport has increased its role in European travel. They are very proud of it.

The latest display is about Barajas airport. This is a triumph of the art of the model maker. Since the opening of terminal four Madrid’s airport has increased its role in European travel. They are very proud of it.The museum is a fascinating insight into what makes the city tick. It attracts on all levels and children of all ages will find something to amuse, interest and inform.

The Museo de la Ciudad is at Calle del Principe de Vergara, 140. Nearest Metro is Cruz del Rayo on line 9. It is open 10:00 to 20:00 Mondays to Fridays. 10:00 to 14:00 at weekends.

Under the trees the temperature dropped sharply, almost causing me to shiver. There, elderly gentlemen played chess on painted checker board tables. Readers relaxed with their newspapers or books. Young mothers sat and watched their offspring. It all seemed rather peaceful, and just what I needed.

Under the trees the temperature dropped sharply, almost causing me to shiver. There, elderly gentlemen played chess on painted checker board tables. Readers relaxed with their newspapers or books. Young mothers sat and watched their offspring. It all seemed rather peaceful, and just what I needed.

I was actually looking at historically important graffiti. I am pleased to report that during my researches I discovered that I was not alone in my ignorance and that some of the paint had actually been cleaned off by an over zealous Parques y Jardines worker just before Herr

I was actually looking at historically important graffiti. I am pleased to report that during my researches I discovered that I was not alone in my ignorance and that some of the paint had actually been cleaned off by an over zealous Parques y Jardines worker just before Herr

The photograph above shows the derelict state of the ticket office that the workmen found. Today it has been restored to its original ceramically tiled glory as envisioned by the first architect of the metro, Antonio Palacios.

The photograph above shows the derelict state of the ticket office that the workmen found. Today it has been restored to its original ceramically tiled glory as envisioned by the first architect of the metro, Antonio Palacios.  Antonio Palacios Ramilo was a Spanish architect whose works can be seen all over Spain. In Madrid his works include the Palacio de Comunicaciones, that wedding cake castle of a building at Cibeles, and the Circulo de Fines Artes and the Rio de le Plata bank, among many others.

Antonio Palacios Ramilo was a Spanish architect whose works can be seen all over Spain. In Madrid his works include the Palacio de Comunicaciones, that wedding cake castle of a building at Cibeles, and the Circulo de Fines Artes and the Rio de le Plata bank, among many others. The station lies on line one, between Iglesia and Bilbao stations and the trains whizz through at high speed. Fortunately, the platform is barricaded from the tracks by thick panels of glass, through which the visitor can view the opposite platform where short films of preMetro Madrid are projected on to screens.

The station lies on line one, between Iglesia and Bilbao stations and the trains whizz through at high speed. Fortunately, the platform is barricaded from the tracks by thick panels of glass, through which the visitor can view the opposite platform where short films of preMetro Madrid are projected on to screens.

Open Mondays to Fridays from 11:00 to 19:00 and Saturdays, Sundays and holidays from 10:00 to 14:00.

Open Mondays to Fridays from 11:00 to 19:00 and Saturdays, Sundays and holidays from 10:00 to 14:00.