By Richard Morley

The snow capped peaks of the Gredos mountains. Part of the "Sistema Central" of Spain's Mountains.

I wrote recently in my post about the source of the Manzanares river that today’s tranquil landscape had been, a long, long time ago, a rather turbulent place. That while today the pink, or Rose Granite lends a colourful hue to the peaceful slopes of the Yelmo, at the time of its formation it was a place of volcanoes and heaving rivers of lava. It’s a nice place today because it’s been a gneiss place for ages. (Geological joke! – Look it up.)

The Manzanares’ source lies in the Sierra de Guadarrama, part of the central system of mountains that stretches from Portugal to just north of Madrid, incorporating the sierras of Gredos, Avilla, and Guadarrama (among several others) and delineates the divide between northern Spain and the south. In geological terms they are quite young mountains. A famous mountaineer, when asked why he wanted to climb a mountain said, “Because it is there”. Me, I want to know why.

Today we tend to think of dramatic geological events in terms of unpronounceable Icelandic volcanoes and havoc inducing tsunamis. That’s because they happen quickly; over days, or even hours. Most geological events happen much, much slower. For us, and the world in general, that’s a good thing. For Spain

Weathered peaks of the Pedriza in the Guadarrama mountains.

Let’s see the events unfold. (But in a really, really simplified form. I don’t want comments telling me that I have forgotten such and such an event. As an old tee-shirt of mine once said, “Geophysicists do it deeper!”, but here I am just scratching the surface.)

Cast your minds back to, oh, let’s say, 600 million years ago. We will have to speculate a bit. I’ve attempted to do the research, but, as I have discovered in a long career in one particular branch of earth studies, if there is one thing that geologists can’t agree on – it’s EVERYTHING! So, there are competing theories. Quite a few of them have had to be formulated relatively recently. After all, it’s just exactly one hundred years since Alfred Wegener, noticing how the coastlines on opposite sides of the Atlantic fitted together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, published the first paper on how the world’s landmasses seemed to drift across the Earth’s surface. Perhaps because he was an astronomer and meteorologist and not a geologist many did not take his ideas seriously. Plus, there were competing theories (the discredited “expanding Earth”) and the fact that there seemed to be no driving mechanism behind the continental movements. They were still arguing about it in the early seventies when I was a student.

But it seems to go a bit like this. Prior to 600 million years ago the World’s landmasses had been forming and reforming into groups until on almost opposite sides of the globe two super continents, one called Gondwana and the other Laurasia, had come into being. Slowly they drifted together and at about 600 million years ago they met and formed the giant extra-super continent, Pangea.

Pangea looked like a letter C, or a very distorted 8. A bit like a knobbly Pac man figure facing right, it’s mouth agape. But think of the 8, bent into a C shape. Where the two halves of the 8 meet, or perhaps where Pac man’s tonsils could be, were a few independent landmasses which had been crushed together and bridged the gap between the two continents. They are known as the Avalonian, the Amorican, and the Iberian plates. You might like to bear in mind the “Iberian” plate. It’s sort of important in this article!

To the east, ie, within the Pac man’s gaping jaw, lay the Tethys sea.

Then several things happened. Firstly, the pressure of Gondwana pushing up into Laurasia compressed bits of the northern continent and pushed them upwards, forming mountains. Today, these mountains are so eroded it’s not easy, except by using reflective seismic techniques, (a bit like sonar on land) to find the evidence, but some can be found in Spain’s north west, on its corner with Portugal, in south east Galicia.

As the southern continent pushed against Laurasia, it subducted, meaning it slid underneath. This, as today can be seen around the Pacific’s rim, leads to volcanic activity. This can be seen in ancient volcanoes found in Spain

Moving forward in time this volcanic activity would lead to a splitting of the left hand side of Pangea. (Incidentally, I write of left and right rather than east or west, north or south, because even though geologists speak of “Laurasia”, “Amorica”, even “Euro-America”, those land masses were nowhere near their present geographical locations – and after which they are named. (Laurasia became, after the splitting off of north America, Eurasia .) All of what I am writing happened when these land masses where deep in the southern ocean. Spain

But I digressed.

The splitting off of the left hand side of Gondwana led to the formation of South America . Parts of Avalonia are found in the British Isles south of Scotland and continue through northern Europe . Other parts are found in eastern Canada , from where it took its name from the Avalonian peninsular in Newfoundland

For the next 250 million years the great continent drifted northwards. 450 million years ago the Tethys sea began to close. So, as Pac man’s mouth slowly closed, the land mass of Laurasia turned clockwise. In the middle of this upheaval the two plates of Iberia France , and you will think that Iberia and France Portugal , Galicia and Northern France . (Remember that little fact!)

Meanwhile Iberia

It was in the Jurrasic, around 180 million years ago, that Pangea began to split up. The Tethys sea was closing rapidly. The Indian plate was sliding across to bump into asia . The Antarctic plate, with Australia and New Zealand North America , was revolving clockwise. What was left of Gondwana, basically Africa, was continuing to push north and the two joined landmasses of Armorica and Iberia

The theory of much of what I have written is pretty common knowledge these days. The Discovery channel and others present documentaries about how these giant plates; the Pacific Plate, the African Plate and so on, are rolling around the earth. These giant plates are, in fact, “cratons”, meaning they are composed of lots of smaller plates that seem to have permanently joined together; the completed parts of a jigsaw puzzle, if you like. It is where the constituent plates rub against each other that we get seismic activity like earthquakes and volcanoes.

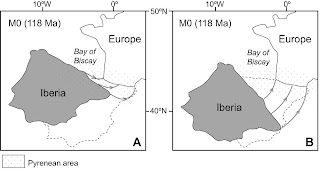

Iberia swivels under France to open up the Bay of Biscay.

For many millions of years the Amorica-Iberian landmass had formed a bridge between Northern Laurasia and Southern Gondwana . About 120 years ago they made their choice and Amorica, with its twin, became a craton of Eurasia . But the forces that had split North America away, first a volcanic rift then the spread of the Atlantic ocean, were pulling on Iberia and the clockwise motion of Eurasia was pulling on Amorica. Eventually they swung apart, but hinged at their southern extremity. This is the, literal, twist in the tail. As Amorica moved north and clockwise, Iberia France , the beginnings of the Pyrenees were formed.

NASA photograph of the Pyrenees. Notice the compression folds as Iberia was pushed into Armorica.

A glance at the geological map above shows the continuation of the north-south oriented western Iberian mountains continuing oriented east-west in Brittany and Normandy in northern France Europe was their love of cider, but it obviously goes much deeper – and further back – than that!

But things did not stop there. Africa, divested of south America, India , Antarctica, continued, and continues, to move north, still pushing into Europe . With Europe now more or less in its current position this northern movement of Africa exerted such pressure that ridges of mountains were formed all over the place. The mechanism is known as the “Alpine Orogeny” (mountain building) and, obviously, the European Alps are its main manifestation, but it is responsible for the rolling south downs of England , the Apennines in Italy and the Atlas mountains in Morocco , Algeria and Tunisia Spain this action is responsible for the Cantabrian mountains, including the Picos de Europa in Asturias and the Sierra Nevada in Andalucía.

Squeezed at both ends the centre of Spain Iberia

The Tethys sea had completely closed up at its eastern end by the land masses of India Mediterranean . By any standard the Mediterranean is a substantial body of water. It has a surface area of 2.5 million square kilometres, an average depth of 1500 metres. It nearly 3000 kilometres from end to end and around a thousand wide, not including its sub seas; the Adriatic, the Aegean and so on. It borders 21 countries and has many important sea routes.

Imagine it empty.

Slightly less than 6 million years ago that happened. In an event named the “Messinian Salinity”, after the city of Messina in Sicily Gibraltar . Within a thousand years, apart from a few very salty lakes, some more than 3Km below present day sea levels, the Mediterranean was dry. And it stayed that way for nearly 700,000 years! The fossil record shows evidence that animals used the dried up sea bed to migrate between the two continents. The mineral record, achieved by studying core drilling samples show typical shore line mineralogy from the sea bed hundreds of kilometres from modern day shorelines.

Almost as abruptly, in geological time-speak, as it had begun, 5.3 million years ago, due to yet more geological shifting, waters once again poured through the straits in an event called the Zanclean Flood. Zanclean is the name geologists give to that era which begins the modern geological age. Geological studies show that the straits of Gibraltar were not the only water course open. There was one through Morocco and another across the Betic Plain, around modern day Seville

These carried water of a much higher volume than is carried over Niagara Falls Niagara ’s rate of flow is just under 2000 cubic metres per second.) However, Niagara’s waters come from the narrow confines of the Niagara river, the waters pouring into the Mediterranean had the force of the entire Atlantic ocean behind them.

Of course, that was not the end of Spanish seismic activity. Since written records began there has been a long history of seismic destruction. To mention the more famous – or infamous, there is the Lisbon

In 1884 the town of Arenas

I take no joy from the fact that, following reading a few reports, I posted on my Facebook page on May 1st this year that Spain Lorca

Earthquakes, having been part of my life for so many years, means that I often get asked to speak about them. By coincidence, I was doing just that on the 12th of August 2007 when news came in that there had been a mild(ish) earthquake in Ciudad Real

I shouldn’t have been surprised. I monitor the website of the Spanish geographic institute which reports on all quakes around the Iberian Peninsular. You can see it here.

That’s the downside of living on top of active geology. The advantages have been enormous. Spain

The carboniferous era laid down coal in Galicia and Asturias Spain Spain Sorbas Spain is Europe ’s largest producer and the second largest in the world.

There’s iron, bauxite, and a long list of other minor stuff. Not much oil sadly. Some oil shale which kept the power stations of Spain running for many years and a small field off the coast of Cantabridgia .

And all that mountain building has given Spain Switzerland , Spain is the most mountainous country in Europe .

The continents will keep moving. Some think that Iberia will become so squashed by Africa’s relentless push that it will be squeezed out into the Atlantic like a geological zit. Perhaps it will become an island drifting who knows where. I read one report that suggested in 30 million years it will be somewhere near where Iceland

Just as a serendipitous postscript I was amused to find a shop specialising in "Geological Jewellery" (if there is such a thing!). Many long eJstablished businesses like to boast of their year of foundation. They are never going to beat this place.

Find decorative geodes, fossil fashion, minerals and meteorites 72, C/Hermosilla. (Near Goya metro.)